Aviation is jargon-ridden and full of acronyms, but our Frequently Asked Questions page cuts through the confusion so you understand the issues.

Who’s Who?

Luton Borough Council owns the Luton Airport site on behalf of the people of Luton. It is often referred to as LBC.

Councils which own airports have to separate themselves from them by setting up an airport-owning company – in Luton’s case this company is called London Luton Airport Ltd, or LLAL, and is 100% owned by LBC.

If the airport-owning company does not have the expertise to run the airport, it appoints a third party to do that – in Luton’s case this is London Luton Airport Operations Ltd, or LLAOL, which is Spanish-owned.

Just to overdo the acronyms, all the parties above often refer the the Airport as London Luton Airport, or LLA.

There is a statutory consultation group called the London Luton Airport Consultative Committee, or LLACC, in which LBC, LLAL and LLAOL staff meet representatives of other local councils and local community groups.

LADACAN – the Luton And District Association for the Control of Aircraft Noise is a community group which sits on the LLACC to represent members’ views and fight for better recognition of the community perspective.

How is aircraft noise measured?

Although everyone knows what noise is, there’s a whole plethora of ways to measure and describe it, which can get very confusing. For the purposes of noise from aircraft, it can all be boiled down fairly simply:

Loudness is measured in decibels (dB) and puts a number on what we hear, which is a challenge because our hearing covers a huge range. By general agreement, an increase of 10dB in peak loudness sounds twice as loud, and most people can detect a loudness change of 3dB – some are more sensitive.

The measure is called Lmax, and a very noisy flight would be 80-90dB Lmax, a noisy one around 70dB, a middling one 60dB, a quieter one 50dB.

Aircraft noise is not continuous, so people also find it useful to describe how often there is such noise (ie how many flights pass per hour or day) and try to combine peak loudness and how often, into one number.

The combined number is a logarithmic average of the noise events over a period (usually 16 hours of day or 8 hours of night) and is also, rather stupidly, expressed in dB but called Leq16h or Leq8h depending on time.

The averaged values might be say 60dB Leq16h in a noisy area close to an airport where flights might sound as loud as 80-90dB Lmax, but the value depends not just on the individual loudness but the number in the period.

Increasing the LAeq value by 3dB would correspond to doubling the noise from each flight or doubling the number of flights, but it’s not the same as the loudness of each flight or indeed any individual noise – it’s an average.

Noise limits and planning conditions

The Civil Aviation Authority (CAA), the government’s aviation regulator, has defined standard positions for measuring peak noise, 6.5km from where an aircraft starts its takeoff run.

Noise Violation Limits (NVLs) set by airports or planning authorities relate to peak noise at those specific monitoring locations.

Departing aircraft may pass over communities before reaching the noise monitoring location; arriving aircraft may pass over communities after the monitoring location – in both cases making more noise that the specified limit. This is permitted: the limit only applies at that monitoring location.

A set of other noise control planning conditions is often needed, such as:

- numbers of flights within defined periods (eg at night or in the day)

- the maximum Leq noise footprint area for a given dB in defined periods

- the product of the aircraft noise classification and the number flown (often called a quota count)

Misleading information

The aviation industry often uses terms in a misleading way – claiming for example that a new engine is half as loud where in fact although it emits half the noise energy, it only sounds 3dB quieter. As indicated above, it would have to be 10dB quieter to sound half as loud.

The industry also tries to pretend that people would not notice a 1dB change in Leq, when of course they would because it would represent an additional number of flights in the average: with 400 flights a day, a 3dB change would correspond to 200 flights, and a 1dB change to 60-70.

Noise contours

The noise averages, or Leq values, can be calculated for different places. They tend to reduce further way from an airport as the planes spread out and climb, and increase as you get closer to the runway.

Based on the calculations, the noisiness can be viewed as a kind of hill: the closer to the airport the higher you climb, and like any other hill, contours can be plotted.

A contour joining all the places close to a runway with the same average noise (eg 60dB Leq) will enclose an area, and the size of that area indicates how widely spread the noise is.

Noise insulation

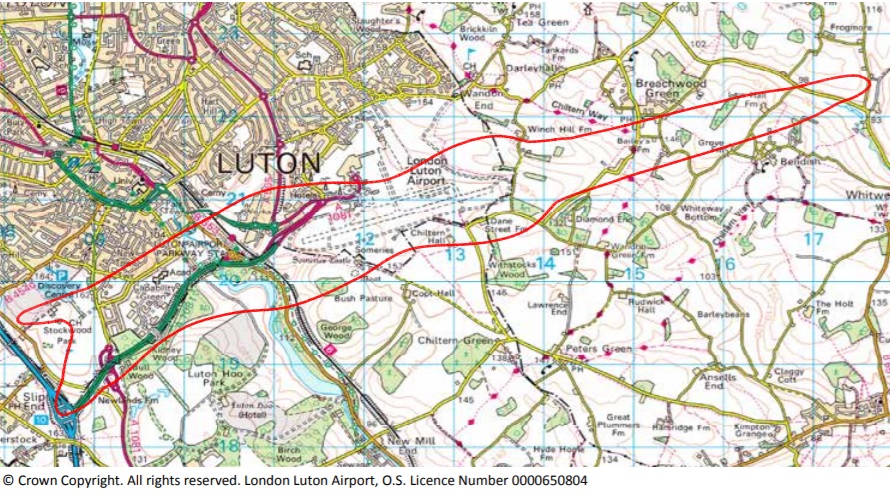

Airports sometimes offer noise insulation to homes located within a given noise contour – an example from Luton’s insulation scheme is shown here:

If your home is in the red contour area they offer you insulation, if not they don’t.

These contours are all computer-generated based on noise models which the airports tend to keep secret – not much use if you want to check them!

When applying for planning permission to change the noise, they re-run the models and the computers then spit out numbers on how many additional homes and offices would fall in a given contour – all very impersonal.

N-numbers

Other contours can be computer-generated to indicate how many flights sounding noisier than a given level will pass over a given location per day.

These are called N-numbers – for example N65 is the number of flights louder than 65dB Lmax (peak noise) at that location in the specified time.

And again, they join these up to create contours linking areas experiencing similar impact.

Aircraft noise affects real people

Different people react to aircraft noise in different ways, depending on:

- how loud an individual flight is

- how long the flight takes to pass

- what time of day or night they occur

- what the background noise levels are like

- how low and visually intrusive the flight is

- whether the overall noise experience has changed

- whether the noise events are all bunched up or spread out

- how often flights affect them at home, at work, in the garden or park

It is completely insulting to represent this as just one number, but industry and government tend to adopt the Leq average because it correlates fairly well to overall annoyance – though the research is very out of date now.

On the next page we show the Flight Tracks around Luton Airport.

For those wanting more detailed information about noise measurement and ways it can be portrayed, we suggest the ICCAN Review of aviation noise metrics and measurement recently produced by the Independent Commission on Civil Aviation Noise – it will certainly help you get to sleep!